If you find this article helpful, please remember this was work to put together and I have animals to feed and vet

A few weeks ago I was going to write a post about the relationship between my path following the War Goddesses and my pop culture interests and involvement in the Sarah Connor Charm School. I hadn’t gotten around to it, because it’s a busy time of year on the homestead and I was supposed to spend my writing time on an article which has a deadline (and I give myself an earlier one so I can get some feed back from a few trusted friends before sending it off). But it’s raining, and while I suppose I could be doing house work I’m not, and the article is in rough draft and I need a break before editing it so…here I am…

Meanwhile, during the time I wasn’t writing that I started to see links posted on FB about some explosion about Pop Culture Worship on the Pagan Blogsphere. It wasn’t happening in any blogs I read nor were any Pagans I know who are students of pop culture (yes, this is studied), in fact, none of them seem to have piped up on it yet. I suspect one is watching for a research paper at this point. ~;p So I didn’t pay much attention until it did land in a blog I do read. I discussed some there, although by the time it landed in another blog I read, my interest in chatting had faded. The first link has a lot of links to much of what was written before, although it seems to have continued going all over the place. I’ve only read a few, mostly just skimmed, most I haven’t.

And I’m not really going to get into the argument. There are too many things that came up that I could, but most seem to partially come from 1) perhaps caring a bit too much about what the fuck other people are doing. Yeah, I can go there, but I’m old and tired now, it doesn’t interest me much unless it affects my work in some way (like liars I have associated with and people who are claiming things about Gaelic culture that is insanely stupid). 2) Most of these opinions are expressed without a real understanding of certain aspects of pop culture studies that, well, I’m too old and tired to go into the entire background of here. It could take books, after all, then I’d have to come around to what has been said and where that fits or doesn’t. The overwhelming concern with pop cultures as “consumerist” is part of why I see no point really getting into it as that both over simplifies pop culture and also forgets the agendas of survival (in a different economic system) behind many of our old stories). There isn’t as much difference between modern pop culture and the popular cultures of the past as I think some people seem to think, just shortening the term doesn’t give it a different meaning. But I’m too old and tired to give 30 years of work in one blog post. 3) This idea is certainly nothing new. I’ve been around too many fucking Discordians and too many “Jungian Archetype” Pagans, often mixed, for far to fucking long to get my panties in a bunch about this. Where were you all talking about this 30 years ago? Really, you’re just discovering this?

So I’m mostly going to discuss this in regards to, well, me…this is my fucking blog after all. And, of course, this post, which was partially planned already, may seem a bit defensive. Oh, well.

Of course, only one of the those blogging might read my blog, maybe. Has links to here anyway. But others might see that this blog mixes pop culture and spirituality, read that I have a Sarah Connor action figure on my gym shrine and such and come away with the idea that I worship Sarah Connor. Sorry, that would be weird (especially as I’ve met Linda Hamilton and it would be all weirdly conflated and how weird is that for her? Hells, it seems to have taken time for her to come to terms with the whole icon thing as it is). So here’s the deal, some of us make personal spiritual connections with pop culture without worshiping them. Deal with it.

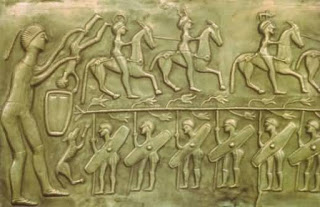

The Sarah Connor figure on my shrine doesn’t represent any Goddess, They are represented by a statue, a modern artist’s interpretation of an Morrígan. “Sarah” is there to be a modern representation of warrior woman, not just this one character but a general, well, archetype. Yes, while I am a hard polytheist about my Gods, I also see the power of archetypes. I don’t worship them either. She’s there to be, as the character is for me, something to strive towards. And it’s important to me to have modern representation, not just those out of the Iron Age. Because I don’t live in the Iron Age.

That, of course, goes with much of what else I do. My primary interest in training on the warrior path is modern, I might like sword training, but for me it’s not as practical as shooting. I try to do both, of course, because it allows me to honor the past and be ready in the present. Mind you, sword training can be practical, as my knees continue to age it might be more so for I might carry a cane as often as I do a gun. But in general, I’d just as soon have the gun too. I’m not role playing.

There seems to be some concept that if we focus on modern pop culture images that They might use it to connect with us. Well, yes. I just don’t see the same problem with that that others seem to have. And I also don’t think we can avoid it. See, I’m of the mind that it happens all the time already. Look at “alien abduction” and the similarities with Fairy encounters of the past. I’m personally not with the Whitley Strieber camp that that means the Folk, let alone the Gods, have been aliens all along. I believe instead the Folk show themselves to people in ways that those people might identify with, as it’s useful. It’s going to happen, we are products of our time. And They are timeless.

Back in the days when my head was sort of stuck in the past, I had two things happen to me. One was a meditation in a warrior path workshop where we were told to approach a mirror and see ourselves as the warriors we wish to become. I actually approached expecting to see myself as my imagining of an Iron Age warrior, but instead I was pretty much dressed much as I was dressed, not much unlike Sarah Connor actually but for colder camping conditions. Unlike as I was then, in MA and not having made peace with guns, I also had firearms. It was a clear reminder to me to stay in the present.

Shortly after that I met one of the War Goddesses. Before this They always appeared archaic. This time, She was wearing a black wool skirt just below the knee, black tights and sensible shoes, a black sweater, neatly tailored black leather jacket and a beret. Same face I knew but the tattooing only faintly showing, same tri-colored hair but shorter and Her braids not as noticeable; She could have been mistaken for a human if one didn’t look closely. I’d been doing research on the IRA at the time, so I recognized this. But I also got the message here, “I am of Ulster at heart, but of all time.” Mostly I still see Them in more archaic garb, but, again, it was a time when I think I could have fallen into too much romance of the distant past and I needed to be reminded not to.

No, She hasn’t appeared dressed as Sarah Connor, but if She did it wouldn’t be the same as me suddenly worshiping the character. After all, She’d have Her own face as I know it and tri-colored braids. It would be simply another form for the Shape-shifter, it would be up to me to reason why. After all this, it might even be a joke. I know better than to take everything seriously now.

Oh, wait, I’ve changed my mind

Yeah, I’m going to run off a few thoughts about the whole “pop culture is different from past popular cultures.” In order to avoid writing the book that this could take, I will probably get a bit disjointed. I also realize this is going to be at least two blog posts to get back to my original plan.

I do not know that there was ever a Goddess actually worshiped by the pre-Christian Irish titled the Morrígan. I don’t know for sure that there were Goddesses named Macha, Badb or Anand or if any would have born the title if They were. I don’t have one single myth. Anyone who calls the Irish literature “mythology” is mistaken. It’s not. You can wish it to be, but it’s not. It’s literature, written by Christian monks. And, at the core, that’s the only thing we really know about it.

We know it correlates to place names, but we don’t know what that means. So we know for some reason Emain Macha exists, but…we have multiple stories about why. (Meyer et al) Ronald Hutton’s take on this is that “It looks as if the authors knew nothing of her except her name, and were inventing stories to go with it.”(Hutton) Now, personally, I don’t believe that they created all these stories out of thin air, but the fact remains we don’t know. All these stories may well be complete fictions created with Biblical and Classical stories in mind, as the Monks certainly knew the latter as well as former,, or they may be older Irish stories with some Biblical and Classical elements added. That the Biblical elements have been included is indisputable, it’s just a matter of what they’re introduced to. The Classical can be debated, are these similarities from common Indo-European threads or directly lifted? This depends on if you follow nativist or anti-nativist thinking…or, like me, tend to be a bit in between. (Wooding)

The debate about the literature and it’s possible connection to pre-Christian ideas is going to go on. Most of us work around our doubts, find what we believe to be the voices of our Gods there, even when we have dismissed notions that any of these clerics purposely tried to keep Pagan ways alive. They had many different agendas, but I doubt that one. Yet, we still find power there because at least part of it is a continuation of the culture, even if the culture we get it from was decidedly Christian. Folklore still told by the people also changed, we have no idea what it was in the centuries before it was recorded even later than the literature. We hope, we pray, and it has meaning for us despite this.

For a lot of scholars, btw, it’s fiction. Interesting, telling of the time it was written, but fiction. I’ve seen Pagans get huffy about it, but that’s what it remains for many who have delved very deeply into it.

The simple truth is that all stories we have, no matter how old, no matter if they were through story telling or written down, have people with agendas behind them. Especially when they get written down. How different is it for a scribe 1000 years ago to keep himself alive by writing a fake history that pleases a king and a writer today who writes something marketable so she can try to make a living? I suppose some will find major differences, but I don’t.

When we read the warrior tales, we see some really repugnant behavior, much which goes against the values expressed in the contemporary legal systems, from the heroes of the tales. This includes Cú Chulainn and Conchobar, of the Ulster cycle (something which I’ve been focused on lately a bit). Does this mean it’s our own sensibilities that are offended? As I said, much would go against the early Christian laws. Or might we think that the scribes had little interest in showing these Pagan warriors in a good light. Is this any different from a screenwriter who believes women should not behave “like men” getting license for one of the very characters he once complained wasn’t his definition of appropriately feminine? There are always agendas behind stories.

But story is always more than the agenda of those who create or tell it. Every person makes it something different. In feminist critique there is the concept of coding (or filtering). Whether it’s ancient tales (this has been used greatly in studies of folk tales, or modern.(Radner) People code things, change the stories in their own heads, in accordance to their own experiences. It isn’t only a gender thing, although that’s where most of the study has been, but also class, culture, sexual orientation, religion….pretty much everything that makes us different from one another. Diana Dominguez uses this method in her study of Medb, looking at how women, as well as the men usually focused on, might have coded these stories.(Dominguez) I think over all studies of Irish literature could benefit from this form of critique, again not just the gender issues. What do people get from it based on their backgrounds is as important to consider as what the creators might have meant.

What I’m coming to, and there could be so much more here, is that the differences between old stories and new ones exist but perhaps not as greatly as some think. It’s just our distance from one as compared to the other that makes it seem so. Rather like how so many people are surprised by every little finding that shows people have always been people, we always seem to think those in the past were greatly different than us. Everyone is different, but that’s just one way we’ve always been the same. ~;)

Seeking Inspiration

I think we’re now way beyond any idea that I’m talking about worshiping Sarah Connor or any other pop culture character. Let’s get to what spiritual meaning might be found separate of worship. Because that’s a big deal for me.

As I said, I believe story is important. It shapes us since were children and, yes, our stories come through TV, movies and comics as much as through books and far, far more than oral telling or even live plays. Some people are geared to it more than others, some spend vast amounts of time role playing, cosplaying, writing fanfic, participating in fan clubs, going to cons. Some of us spend hours reading media critique and writing it. There are people who are not mindful of their media intake at all, perhaps the majority. But some of us know we are affected. We also know others are affected and we worry about it.

Yeah, some of that’s a “woman thing.” And I think that’s another issue that comes up for me. While men on a Gaelic warrior path have tons of old literature depicting their heroes as heroes, although I do hope they question some of the “heroic” acts described, you know such as rape, as I woman I’m not left with much. Despite the popular belief that there are lots of women warriors to be found, there really aren’t that many. And the one who has the most material about her is the villain of the piece, although I personally code her as more heroic than the Ulstermen she fights, all things considered and Dominguez”s study gives lots of reasons why. There are a couple of other women warriors who show heroism, one you’ll find in some links I’ve given already, but their tales are very short. One really is no more than a paragraph. This, btw, is the topic of the article I have been working on, I’ll let you know if it gets published.

So along with also looking for modern day role models, we sometimes just looking for role models. Any. And we’re not going to just be looking in the past. Are there real life ones we could be looking to instead, shit yeah! In fact, the Sarah Connor Charm School has developed a strong focus for honoring such women. But Sarah Connor sums up all of that in one fictional package. And, of course, it brings up that she isn’t completely fictional, because she’s all of us. In all of us. Yes, including the paranoid conspiracy theory parts, in at least some of us. *ahem* Again, there’s that archetype thing.

I feel I’m in pretty good company here. After all, while we are not a “Gaelic Heathen warrior group” as I’m told someone described us on a Pagan radio podcast, many CR women who walk the warrior path seem to be interested. The reality is that it a very mixed bag, with many of our most active members being Christian. On the academic side, Dominguez has also written about modern warrior female warrior icons, “It’s Not Easy Being a Cast Iron Bitch”: Sexual Difference and the Female Action Hero and Tough and Tender, Buff and Brainy: A New Breed of Female Television Action Hero Blurs the Boundaries of Gender. Because we need to explore what the warrior woman means to us and to the culture.

This is turning out long, I have already accidentally published it and those reading on feeds may well have too much insight to my strange habit of stealing my own FB posts as notes for a blog. ~;p I intend to actually get back to the original post I was going to make in a separate post (EDIT: which is now up: An Morrígan and Sarah Connor: Pt. 2 Warrior Cults and Charm Schools). I guess I got sucked into the way more than I thought I would, but I’m leaving the above, where I claim I won’t do that, where it is. (EDIT also Part 3: Our Gods and Heroes in Pop Culture takes a look at the reverse issue) (EDIT: also Part 4: Training)

Oh, another note, of all the posts on this blog, the Wonder Woman one is more popular than all the other combined, by many times. I do think that tells us something, too.

———————

Kuno Meyer, trans. ‘The Wooing of Emer’“Tochmarc Emire,” Archaeological Review 1, 1888, English Irish para. 30 pg. 151-152,

Geoffrey Keating (Seathrún Céitinn), Foras Feasa ar Éirinn: The History of Ireland Vol. 2, David Comyn, Patrick S. Dinneen, eds., London: David Nutt, for the Irish Texts Society, 1902–1914 English Irish Section 28

John O’Donovan ed. and trans., Annala Rioghachta Eireann: Annals of the kingdom of Ireland by the Four Masters, from the earliest period to the year 1616. Library of the Royal Irish Academy and of Trinity College Dublin Pt 1 English, Irish M4505-M4546

Edward Gwynn, ed. The Metrical Dindshenchas Vol. 4, Dublin: Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, 1991 (org. 1906) English Irish Poem 12

Ronald Hutton, The Pagan Religions of the Ancient British Isles: Their Nature and Legacy, Cambridge, MA: Blackwell Publishers, Inc., 1995 pg. 154

Jonathan M. Wooding’s “Reapproaching the Pagan Celtic Past – Anti-Nativism, Asterisk Reality and the Late-Antiquity Paradigm” Studia Celtica Fennica VI, Finnish Society for Celtic Studies, 2009 pg. 51-74

Joan Newlon Radner, ed., Feminist Messages: Coding in Women’s Folk Culture, Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1993

Diana Dominguez. Historical Residues in the Old Irish Legends of Queen Medb: An Expanded Interpretation of the Ulster Cycle, Lewiston, NY: The Edwin Mellen Press, 2010

copyright © Saigh Kym Lambert

n in the literature as a whole.

n in the literature as a whole. In a short time, possibly today,

In a short time, possibly today, sort of a clean-up although that term was not considered particular seemly and properly Christian by the clerics either. (McCone, West) There is, of course,

sort of a clean-up although that term was not considered particular seemly and properly Christian by the clerics either. (McCone, West) There is, of course,

As I wasn’t writing much about Gaelic spirituality at the time I started this blog, having started at a time of conflict, flux and burn out in the community and taking things more private for awhile, I have realized it might seem a sudden switch to some of my readers. While the intent of this was always to be about various aspects of the warrior path in my life and how they came together, the focus had been on fitness, self-defense and popular culture. That itself might seem quite a mix to some. But it really is in my interest in the warrior ways of ancient Ireland and Scotland that all those things come together, the physical training and the importance of story.

As I wasn’t writing much about Gaelic spirituality at the time I started this blog, having started at a time of conflict, flux and burn out in the community and taking things more private for awhile, I have realized it might seem a sudden switch to some of my readers. While the intent of this was always to be about various aspects of the warrior path in my life and how they came together, the focus had been on fitness, self-defense and popular culture. That itself might seem quite a mix to some. But it really is in my interest in the warrior ways of ancient Ireland and Scotland that all those things come together, the physical training and the importance of story. furniture out of the way (come spring most of it will be moved completely out), we put down padded flooring, moved in the weights, benches, heavy bag. We added a pull-up and dip tower, as I have given up, for now, on finding the perfect bed frame to turn on it’s side. When things are moved out more we’ll have more open space, especially to work the bag, and probably get more equipment over time.

furniture out of the way (come spring most of it will be moved completely out), we put down padded flooring, moved in the weights, benches, heavy bag. We added a pull-up and dip tower, as I have given up, for now, on finding the perfect bed frame to turn on it’s side. When things are moved out more we’ll have more open space, especially to work the bag, and probably get more equipment over time.

McCone finds it likely that there were men who were never given inheritance who remained. In the tales Fionn is an example. He doesn’t speculate about women in the bands, but Nagy notes those associated with Fionn himself, especially his fosterers. (The Wisdom of the Outlaw) In most of the tales we have of women involved, with the exception of Fionn’s fosterers and Aoife, who is so named (Scáthach isn’t, but is clearly a woman warrior who is Outside the culture in question), the women likewise are only ban-fhénnid for the time they must be for revenge. (

McCone finds it likely that there were men who were never given inheritance who remained. In the tales Fionn is an example. He doesn’t speculate about women in the bands, but Nagy notes those associated with Fionn himself, especially his fosterers. (The Wisdom of the Outlaw) In most of the tales we have of women involved, with the exception of Fionn’s fosterers and Aoife, who is so named (Scáthach isn’t, but is clearly a woman warrior who is Outside the culture in question), the women likewise are only ban-fhénnid for the time they must be for revenge. (