Category: Cu Chulainn

Excerpt from “The War Goddess’s Bitch”

This is from my article in Air n-Aithesc Vol III, Issue 1 currently available in hard-copy or e-copy from this link. Unlike previous excerpts, this in not the beginning of it, as I began with a dream sequence that would be too long for a lead in and I don’t want to post only part of. The article is a continuation of my exploration of the fénnidecht wolf-warrior path, specifically how I follow it as a devotion to the Morrígan and some material on female werewolves, weredogs and dog-heads.

This is from my article in Air n-Aithesc Vol III, Issue 1 currently available in hard-copy or e-copy from this link. Unlike previous excerpts, this in not the beginning of it, as I began with a dream sequence that would be too long for a lead in and I don’t want to post only part of. The article is a continuation of my exploration of the fénnidecht wolf-warrior path, specifically how I follow it as a devotion to the Morrígan and some material on female werewolves, weredogs and dog-heads.

The War Goddess’s Bitch

Wolf-warrior cults are usually attributed to male Gods. The Vedic Indra and Rudra, the Germanic Odin and the Greek Apollo Lykeios have all been associated with wolfish warrior bands.[i] Kershaw states that there are no known Celtic Gods associated with warbands, other than seeing a similarity between Finn and the Fíanna and Rudhra and the Maruts.[ii]Kershaw also mentions McCone’s pairing of Ódinn/Týr and Lug/Núada as teuta/koryos(civilization/warband or wild) God pairings.[iii] Lug is certainly a candidate for such a warrior cults: His relationship to both Cú Chulainn and Finn, adds to this possibility.[iv]While I would not argue against Lug, Finn (as a God, although I tend to focus on his nature as a semi-divine hero) or other Gods as having had such cults, I believe that it is as likely that the Goddesses who fall under the title the Morrígan were also likely to have been the Divine leaders of such cults.

The Morrígan’s interest in Cú Chulainn, the Hound of the Smith, is evident throughout the TBC and related Ulster tales. Some see their relationship as confrontational, often confusing. Epstein has speculated that She may indeed be his patron Deity.[v] Epstein noted that the seemingly adversarial nature of Her relationship with Cú Chulainn can be seen as an effort to strengthen his glory, as I have also explored.[vi] Epstein specifically brought up the similarities between his canine nature, which goes far deeper than just a name, and the Norse ulfheðnar (“wolf coats”) and berserkr (“bear coats”) who followed Odin. She speculated that this might hint at an ecstatic cult dedicated to an Morrígan.[vii]

This ecstatic, shape-shifting nature suggests such a cult as well as the obvious canine connection. Cú Chulainn’s name connects him with canines: he is the Hound, actually acting as Culainn’s guard dog as a boy, to replace the dog he killed.[viii] Yet his form of shape-shifting, his ríastrad (warp spasm), is not decidedly canine. By killing the guard dog and then assuming the dog’s role, Cú Chulainn was transformed completely into a hound not only for his time of service to the Smith but for the rest of his life.[ix]He was always a hound. He was just wilder, more dangerous, rabid, when he transformed and he described himself as having canine fury in Tochmarc Emire.[x]His identity as the Hound was so significant that when St. Patrick conjured Cù Chulainn’s specter in order to convert Lóegaire, the king of Ireland, the specter’s canine nature convinced the king that the specter was truly Cú Chulainn.[xi]

Cú Chulainn’s story gives no indication of him as part of a warband. This lack is likely related to animosity between the church and such warriors they called díberga (marauders, brigands).[xii] It is notable that the ecstatic transformation and the connection to a Deity were revealed at all. When the stories of warbands were finally set down, the Fíanna seem quite divorced from the earlier, negative, accounts of the díberga, that displayed little association with either shape-shifting or Deity.[xiii] The association with hounds is strong in the stories around Finn Mac Cumhail. There are many members of the Fíanna with canine names. However, the fénnidi’s own canine nature is only hinted at vaguely. Finn did have the hood of Crothrainne, which allowed him to turn to hound or stag, yet there is little evidence of him using it.[xiv]In one alternative tale of the birth of Bran, Finn was his father by a woman enchanted into the form of a bitch. One might choose to speculate that he used the hood at that time.[xv]

Read more by purchasing AnA here

[i] Kris Kershaw, The One-eyed God: Odin and the (Indo-) Germanic Männerbünde, Journal of Indo-European Studies, Monograph No. 36., Washington D.C.: Institute for the Study of Man Inc., 2000, such Gods and Their cults are the subject of the entire study, however particular interest might rest in ch. 9 “Odin Analogues” pg. 182-200; Dorcas Brown and David Anthony, “Midwinter Dog Sacrifices at LBA Krasnosamarskoe, Russia And Traces of Initiations for Männerbünde” Paper presented, Conference: Tracing the Indo-European: Origin and migrations. Roots of Europe Research Center, University of Copenhagen, Denmark Dec 11–13, 2012.[ii] Kershaw, The One-eyed God, pg. 186.[iii] Kershaw, The One-eyed God, pg. 195.[iv] C. Lee Vermeers discussed his relationship with Lú Ardáinmór as a lycanthropic God in a blog post http://faoladh.blogspot.com/2013/05/what-i-domy-own-gods-part-one-my-upg-so.html and has also talked about Apollo as a Wind-Wolf God, http://faoladh.blogspot.com/2011/05/gods-and-goddesses-of-werewolves-wind.html[v]Epstein, “War Goddesses,” Ch. 2.[vi]Epstein, “War Goddesses,” Ch. 2; Lambert, “Musings on the Irish War Goddesses;” also further explored in my blog post “The Morrígan and Cú Chulainn part 1: On Saying ‘No.’”[vii]Epstein, “War Goddesses…,” Ch. 3.[viii]TBC Rec 1 pg. 17-19,140-142; TBC:BOL pg. 23-25, 160-163.[ix] McCone, “Aided Cheltchair Maic Uthechair: Hounds, Heroes and Hospitallers in Early Irish Myth and Story.” Ériu 35, 1984 pg. 8-11, I discuss this act as being linked to wolf-warrior initiations in “Going Into Wolf-shape.”[x]Bernhardt-House, Werewolves, Magical Hounds, and Dog-headed Men, pg. 174, 343.[xi]Joseph Falaky Nagy, Conversing with Angels and Ancient: Literary Myths of Medieval Ireland, Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1997, pg. 274.[xii] Kim McCone, “Werewolves, Cyclopes, Díberga and Fíanna: Juvenile Delinquency in Early Ireland” Cambridge Medieval Celtic Studies, issue 12, 1986, pg. 3-4; Sharpe, “Hiberno-Latin Laicus, Irish Láech and the Devil’s Men,” Ériu 30, 1979, pg. 80-87.[xiii]Kim McCone, “Werewolves, Cyclopes, …”, pg. 3-4; I discuss other links between the díberga and the Fíanna and canine nature further in “Going Into Wolf-shape” as well.[xiv]Kuno Meyer, ed. and trans., “The Finn episode from Gilla in Chomded húa Cormaic’s poem “A Rí richid, réidig dam” Fianaigecht, 1910, Hodges, Figgis & Co., Dublin, Ireland, pg. 51. http://archive.org/details/fianaigechtbeing00meye[xv]As we’ll discuss shortly, Bran and Sceolang are more commonly said to be the children of Finn’s aunt, however, this tale is noted by Bernhardt-House, Werewolves, Magical Hounds, and Dog-headed Men, pg. 196.

Copyright © 2016 Saigh Kym Lambert

Wolf Copyright © 2002 Aaron Miller, based on Newbigging Leslie stone

Moving things around and more re-self-publishing

Some, maybe, have noticed that I have moved the website to http://dunsgathan.net/feannog/ the old folder will forward you there from old links.

At the same time, I have also created a page to house links (this link goes to said page) to PDFs of articles originally published in Air n-Aithesc (this link goes to the magazines page)

At this time the page has “‘By Force in the Battlefield’: Finding the Irish Female Hero” and “Going into Wolf-Shape” up. Will get the other two I have ownership of up in the near future.

Excerpt from “Chase to Nowhere: Thoughts on Fénnidecht Rites of Passage”

As I had mentioned, I thought I’d actually post this excerpt with the issue freshly released. This is from the newest issue of Air n-Aithesc vol. II issue 1, which can be purchased in either hard copy or digital here.

Chase to Nowhere: Thoughts on Fénnidecht Rites of Passage

The tales of Finn Mac Cumhail’s Fíanna capture the imaginations of many following Gaelic ways, but only a few have really explored the possible realities behind them. Many approaching the cultural material dismiss the tales as purely fictional or as retellings of stories of Gods made human for Christian audiences. While Finn may have been originally a God of the A few in the Pagan community have claimed these bands comparable to modern special forces while claiming the “tribal warriors” would have been “regular army.”[i]Perhaps this is due to how extreme some seem to feel the initiatory testing, which is below, to be. However, if we were to make a modern analogy, it would be far more accurate to compare the Fíanna with the Boy Scouts; violent Boy Scout troops which not every boy survived to become “tribal díberga,” which is usually translated as “brigands,” we are speaking of very violent Boy Scouts, often with vows of vengeance to carry out. [ii] The modern Irish “díbheirg” means “wrath” or “vengeance,” which points to the importance of this aspect.[iii]

The tales of Finn Mac Cumhail’s Fíanna capture the imaginations of many following Gaelic ways, but only a few have really explored the possible realities behind them. Many approaching the cultural material dismiss the tales as purely fictional or as retellings of stories of Gods made human for Christian audiences. While Finn may have been originally a God of the A few in the Pagan community have claimed these bands comparable to modern special forces while claiming the “tribal warriors” would have been “regular army.”[i]Perhaps this is due to how extreme some seem to feel the initiatory testing, which is below, to be. However, if we were to make a modern analogy, it would be far more accurate to compare the Fíanna with the Boy Scouts; violent Boy Scout troops which not every boy survived to become “tribal díberga,” which is usually translated as “brigands,” we are speaking of very violent Boy Scouts, often with vows of vengeance to carry out. [ii] The modern Irish “díbheirg” means “wrath” or “vengeance,” which points to the importance of this aspect.[iii]warriors.” That in other texts as well as legal tracts such warriors were also known as “

war bands, it is clear such warriors also existed.

As I discussed in “Going into Wolf-Shape,” such adolescent bands were found throughout Indo-European cultures and, likely, far earlier. [iv] “Everyone is a fénnid until he takes up husbandry,” Cormac Mac Airt noted to his son, although it is clear that “everyone” really meant males, mostly noble, like themselves.[v] Boys would go from fosterage to wilderness at 14, then those who received their inheritances would rejoin society about the age of 20.[vi] It might be noted that this is the age period that modern neurobiology has recently shown is a time of extreme erratic risk taking, especially for boys. [vii]As one might expect when sending high impulse risk takers off to fight one another in the wilderness, not all of them survived, but there may well not have been sufficient inheritance for all. Some may have had to or even chosen to remain in the wilderness, just as we see Finn and others do in the literature. McCone has noted that early on some continental bands would move on from their overpopulated homelands to found new settlements.[viii] Where and when this wasn’t possible, it seems some remained in the wilderness until they were likely killed in fighting or managed to die of old age.[ix]

We can only speculate whether any may have chosen to remain in what seems a Pagan lifestyle well into the Christian era, [x] out of preference. While I hope some of what I share may help develop training and path work for teenagers, my own interest is with the more chronic Outlaws, which are clearly the “norm” in heroes of the Fenian literature and likely also existed in reality.[xi] I believe that these Outlaw bands have much to offer for those of us who realize we cannot replicate early society itself; or who may realize that we fit better in the wilderness than we ever would have in early Christian or even pre-Christian, what little we know of it, society.

The question becomes how we move into this liminal state.

You can read the rest by purchasing Air n-Aithesc vol. II issue 1

[i] Such a conversation took place in a Facebook group I run, Clann na Morrígna, but I have heard or read it in many conversations over the past couple of decades.[ii] Richard Sharpe, “Hiberno-Latin Laicus, Irish Láech and the Devil’s Men,” Ériu 30, 1979; Kim McCone, “Werewolves, Cyclopes, Díberga and Fíanna: Juvenile Delinquency in Early Ireland” Cambridge Medieval Celtic Studies, issue 12, 1986; one example is Whitley Stokes, ed. and trans., “The Destructionof Da Derga’s Hostel” (Togail Bruidne Da Derga), Revue Celtique. volume 22, (1901) pg. 7, 29-30; legal tracts are also noted in D. A. Binchy, “Bretha Crólige,” Ériu 12, 1938, pg. 41, Fergus Kelly. A Guide to Early Irish Law, Dublin: Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies (School of Celtic Studies), 2001, pg. 10, 60[iii] Dónall P. Ò Baoill, ed., Foclóir Póca , Dublin: An Gúm, 1992, pg 338; My thanks to C. Lee Vermeers for noting this in the review of this essay for Air n-Aithesc.[iv] Saigh Kym Lambert “Going into Wolf-Shape,” Air n-Aithesc Volume 1 Issue 1 Imbolc 2014, pg. 29-50[v] “fénnid cách co trebad” Kuno Meyer, The Instructions of Cormac mac Airt, RIA Todd Lecture 15, Dublin 1909, pg 46, 31-10, C. Lee Vermeers, Teagasca: The Instructions of Cormac Mac Airt, Faoladh Books, 2014, including footnote 346, pg. 77-78[vi] McCone, “Werewolves, Cyclopes…,” pg. 11-19; the specific age is noted by McCone, “The Celtic and Indo-European origins of the fían,” Sharon J. Arbuthnot and Geraldine Parsons, eds., The Gaelic Finn Tradition, Dublin: Four Courts Press, 2012, pg. 17-18; Joseph Falaky Nagy. The Wisdom of the Outlaw: The Boyhood Deeds of Finn in Gaelic Narrative Tradition,Berkeley: University of California Press, 1985, pg 20-21[vii] B.J. Casey, B.E Kosofsky, PG. Bhide, eds., Teenage Brains: Think Different?, Switzerland: Kargar Publishers, 2014 (I admit to only reading portions and that it is quite over my head, but for those who are working with teens, I believe it may be a very important study)[viii] McCone, “The Celtic and Indo-European origins of the fían,” pg. 23-27[ix] McCone, “Werewolves, Cyclopes…,” pg. 11; McCone, “The Celtic and Indo-European origins of the fían,” pg. 17-18[x]McCone, “Werewolves,….” pg. 2-3; Sharpe , “Hiberno-Latin Laicus, Irish Láech and the Devil’s Men,” pg.83-92, Katharine Sims, “Gaelic Warfare in the Middle Ages,” in Thomas Bartlett and Keith Jeffery eds., A Military History of Ireland, New York: Cambridge University Press, 1996, pg. 100-101

Copyright © 2015 Saigh Kym Lambert

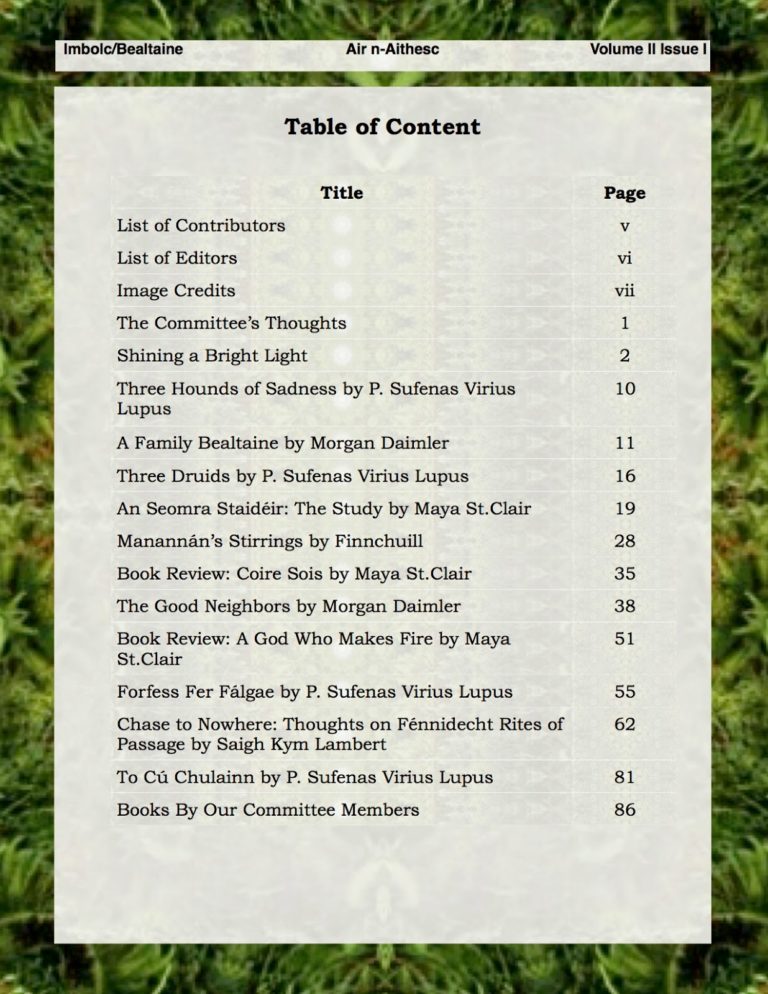

Biannual Publication Announcement – Air n-Aithesc vol. II issue 1

The Imbolc/ Bealtaine 2015 issue of Air n-Aithesc is out now and you can order at the link!

The table of contents is below so see what all is offered. More poetry and prose from PSVL, two articles by Morgan Daimler, an article from Finchuill and book reviews and An Seomra Staidéir from Maya St.Clair.

My article this issue is “Chase to Nowhere: Thoughts on Fénnidecht Rites of Passage” which discusses ideas gleaned from the literature and other sources about the very non-linear rites which might have been associated with the Irish warbands and some ideas about modern incorporation.

Excerpt from “Going into Wolf-Shape”

This is my last of the excerpts from past issues of Air n-Aithesc that I have to share. I have previously posted excerpts from “Muimme naFiann: Foster-mother of heroes” and ‘“By Force in the Battlefield”: Finding the Irish Female Hero’. The rest of this one can be found in the first issue, Vol 1, Issue 1.

The next issue should be out at Imbolc, in just a few weeks. I will try to post excerpts in a more timely manner at that point. ~;) Or maybe I’ll even blog something else. ~:p

The next issue should be out at Imbolc, in just a few weeks. I will try to post excerpts in a more timely manner at that point. ~;) Or maybe I’ll even blog something else. ~:p

Going into Wolf-Shape

Humans have lived with dogs for possibly somewhere between 18,800 and 32,100 years, earlier than previously believed.[i]Given highly social nature of both humans and canines and our mutual ability to hunt in groups requiring good communication skills, it seems natural that the relationship would have started when we were hunter-gatherers. Early Neolithic dog burials in Siberia suggest that during this period dogs held an high status not far below humans, beyond their “utilitarian” usefulness.[ii] How natural the relationship is between humans and canines is something most who live with dogs would readily argue, our ability to relate is a given for us. Science has been proving this point, communication and emotional response are strong and similar.[iii]It would be more amazing if humans and wolves—for dogs are wolves who choose to adapt to live in human packs—had not bonded.

There is a great deal of lore and history regarding the importance of dogs among the Gaelic and other Indo-European cultures. Recent genetic testing has revealed that the rose-eared sighthound originated among the Celtic people.[iv] This ancient hound was the ancestor of the modern Greyhound, the Scottish Deerhound, as well as the Galgo Español, which is probably very similar to the ancient hounds. The warrior and the canine are repeatedly linked in Irish lore. One Irish term for wolf, “mac tire” (literally “son of the land”), seems to have first meant a “vagabond warrior” came to primarily mean “wolf.”[v] Many warriors and kings bore “hound” or “wolf” in their names.[vi] The most recognized is Cú Chulainn, who, as a child, took the very role he became named for, “Culainn’s hound,” after killing the smith’s original guard dog in self-defense.[vii] The Fíanna were renowned for their hunting hounds.[viii]

Read the rest by purchasing Air n-Aithesc Vol 1, Issue 1

[i] Elizabeth Pennisi, “Old Dogs Teach a New Lesson About Canine Origins” Science Magazine Vol. 342 no. 6160, November, 15 2013 http://www.sciencemag.org/content/342/6160/785.full

[ii] Robert J. Losey, et al “Burying Dogs in Ancient Cis-Baikal, Siberia: Temporal Trends and Relationships with Human Diet and Subsistence Practices,” PLoS ONE 8(5) 2013 http://www.plosone.org/article/info:doi/10.1371/journal.pone.0063740?

[iii] Gregory Berns, How Dogs Love Us: A Neuroscientist and His Adopted Dog Decode the Canine Brain, New Harvest, 2013

[iv] Heidi G. Parker, Lisa V. Kim, Nathan B. Sutter et al, Genetic Structure of the Purebred Domestic Dog Science, 21 May, 2004: Vol. 304 no. 5674, pg. 1160-1164 https://www.princeton.edu/genomics/kruglyak/publication/PDF/2004_Parker_Genetic.pdf

[v] Kim McCone, “Varia II.” Ériu 36, 1985 pg. pg. 173

[vi] Joseph Falaky Nagy, The Wisdom of the Outlaw: The Boyhood Deeds of Finn in Gaelic Narrative Tradition, Berkeley: University of California Press, 1985, pg. 44, although far more is in this pages notes 19-22 found on 243-245; McCone, “Aided Cheltchair Maic Uthechair pg. 1-30, especially noted on pg. 12-14

[vii]Cecile O’Rahilly, trans., Táin Bó Cúalngefrom Book of Leinster Dublin: Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, 1967 English http://www.ucc.ie/celt/published/T301035/index.html Irish http://www.ucc.ie/celt/published/G301035/index.html pg. 23-25, 160-163; O’Rahilly, trans. Táin Bó Cúalnge, Recession 1 Dublin: Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, 1976 English http://www.ucc.ie/celt/published/T301012/index.html Irish http://www.ucc.ie/celt/published/G301012/index.html pg. 17-19,140-142

[viii] J. R. Reinhard and V. E. Hull, “Bran and Sceolang,” Speculum 11, 1936, pg. 42-58, Nagy, The Wisdom of the Outlaw, pg. 44, 95-97

Copyright © 2014 Saigh Kym Lambert

Excerpt from “Muimme naFiann: Foster-mother of heroes”

I’ve not blogged for awhile and am not sure when I will again. My writing focus was on getting a new submission for the next Air n-Aithesc and since submitting it we’re trying to catch up on winterizing here, the flu had floored me during the time I had  hoped to be doing most of this. As I have my submission for the summer issue done (for the most part, current reading may make for a few alterations), I am hoping to focus on cobbling some of this stuff I’ve been putting into articles back into Teh Project which, you know, it was all stolen from to begin with. ~;p (ETA: also need to get in some CEUs and will probably rewrite some fitness stuff specifically focused on the training program) So….I figured I’d copy fellow AnA writer Morgan Daimler and post an excerpt from my article “Muimme naFiann: Foster-mother of heroes” in the current issue. That would be Air n-Aithesc Volume I Issue II Lughnasadh/Samhain which you can order right at that link should you wish to read the rest…

hoped to be doing most of this. As I have my submission for the summer issue done (for the most part, current reading may make for a few alterations), I am hoping to focus on cobbling some of this stuff I’ve been putting into articles back into Teh Project which, you know, it was all stolen from to begin with. ~;p (ETA: also need to get in some CEUs and will probably rewrite some fitness stuff specifically focused on the training program) So….I figured I’d copy fellow AnA writer Morgan Daimler and post an excerpt from my article “Muimme naFiann: Foster-mother of heroes” in the current issue. That would be Air n-Aithesc Volume I Issue II Lughnasadh/Samhain which you can order right at that link should you wish to read the rest…

Muimme naFiann: Foster-mother of heroes

When the subject of women warriors come up, Scáthach, Cú Chulainn’s teacher, is one of the first noted, along with Medb. Yet even more so than Medb, Scáthach’s story is not her own but a very brief part of Cú Chulainn’s. Much of what is “known” about her today is embellishment. The idea that she is the eponymous Goddess of the Isle of Skye, [i] is a Goddess of War, the dead and even blacksmiths is found repeated within Pagan sources.[ii] However, while some of these concepts, like the association with Skye, did come about late within Gaelic culture, the others appear to have developed even later outside of the culture, primarily within the Pagan community.[iii]

What we do know about her is that she taught warriors, most notably Cú Chulainn, and had a gift of prophecy. And in this she is not alone, for Finn Mac Cumhail’s lesser-known foster-mother(s), especially Bodbmall, shared similar traits. Nagy stated, “…it would seem that Bodbmall, Búanann, and Scáthach are all multiforms of a supernatural martial foster-mother figure who appears in various contexts.”[iv]We have no stories for Búanann. Scáthach is called Scáthaig Buanand in one version of the Táin Bó Cúalnge, which O’Rahilly translates as “Scáthach the victorious.”[v] The name, however, appears in the Sanas Cormaic (“Cormac’s Glossary”) described as “muimme nafiann”(“foster-mother of heroes”) and related to the role of Anann as mother of the Gods.[vi]Anann is one of the Daughters of Ernmais, the one usually identified as the Morrígan.[vii]

Many scholars do read these foster-mothers as supernatural beings, although seldom as actual Goddesses. [viii] Certainly, Scáthach’s distant and hard to reach land and Finn’s fosterers’ wilderness hide-outs as well as their powers both as a warriors, often seen as unnatural for women, and as seers indeed mark them as Otherwordly.[ix] Scáthach’s title of “Búanann,” and the name’s connection with the Goddess Anann, may make Scáthach seem to be the Goddess. Likewise, a possible etymological relationship between the names Bodbmall and Badb raises the question as to whether she is supposed to be this War Goddess.[x]

Read the rest by purchasing Air n-Aithesc Volume I Issue II Lughnasadh/Samhain

[i] There are a multitude of examples. Caitlin Matthews directly uses these words to describe her in several books, for example The Elements of the Celtic Tradition, Element Books, 1989, pg. 76.[ii] I will not pick out one source for much of this, as where any of it came from originally is impossible to say. A quick online search brings up thousands of websites, often directly repeating each other with no further sourcing.[iii] Isle of Skye part has shown up even in somewhat academic sources. (James MacKillop. Dictionary of Celtic Mythology, New York: Oxford University Press, 1998, pg. 410 for example) How old a connection this was and when Scáthach became connected to the MacDonald fort Dun Scaith is difficult to determine. The earliest reference I found to that she was on Skye was in Macpherson’s “Ossian” inventions of the mid-18th century where he places her at the site and gives Cú Chulainn the Dun in another tale.(James Macpherson, The poems of Ossian, tr. by J. Macpherson. To which are prefixed dissertations on the era and poems of Ossian, Oxford University Press, 1805, pg. 149; Macpherson, Hugh MacCallum, John MacCallum, “Conlaoch,” An original collection of the poems of Ossian, Orann, Ulin, and other Bards, who flourished in the same age, Watt, 1816, pg. 153-158; John Gregorson Campbell also includes this location in recounting Macpherson’s version of “Conlaoch” in The Fians: or Stories, Poems & Traditions of Fionn and His Warrior Band, Elibron Classics, 2005 (org. pub. Date 1891), pg. 6) Stokes determined that the similarity between the Gaelic term for the Isle of Skye (An t-Eilean Sgitheanach) and Scythia (Scithia) was all that caused this connection, which he notes as popular at the time. (Whitley Stokes, “The Training of Cúchulainn,” Revue Celtique 29, 1908, pg. 109 https://archive.org/details/revueceltiqu29pari).[iv] Joseph Falaky Nagy, The Wisdom of the Outlaw: The Boyhood Deeds of Finn in Gaelic Narrative Tradition,Berkeley: University of California Press, 1985, pg. 264, footnote 13 following from pg. 102.[v] Cecile O’Rahilly, trans. Táin Bó Cúalnge from Book of Leinster Dublin: Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, 1967, pg. 95, 231 Irish http://www.ucc.ie/celt/published/G301035/index.html English http://www.ucc.ie/celt/published/T301035/index.html[vi] John O’Donovan, ed. and trans. (with notes and translations from Whitley Stokes) Sanas Cormaic Calcutta: O. T. Cutter for the Irish Archeological and Celtic Society, 1868, http://books.google.com/books?id=rX8NAAAAQAAJ&source=gbs_navlinks_s pg. 17;Whitley Stokes, ed., ‘Cormac’s Glossary’ in Three Irish Glossaries, London: Williams and Norgate, 1862 http://www.ucd.ie/tlh/text/ws.tig.001.text.html pg. 6; see also Nagy Wisdom of the Outlaw, pg. 102; Angelique Gulermovich Epstein, “War Goddess: The Morrígan and her Germano-Celtic Counterparts” dissertation, University of California in Los Angeles, 1998 ch. 2.[vii] Epstein, “War Goddess,” ch.1; Kim Heijda, “War-goddesses, furies and scald crows: The use of the word badb in early Irish literature” thesis, University of Utrecht, Feb. 27, 2007 http://igitur-archive.library.uu.nl/student-theses/2007-0620-200703/UUindex.html pg. 34; Robert A. Stewart MacAlister, ed. and trans., Lebor Gabála Érenn: The Book of the Taking of Ireland, Vol IV. Dublin: Irish Text Society, 1941 http://www.archive.org/details/leborgablare04macauoft pg. 103, 130-131, 160-161, 188-189, I also discuss Anann as the Morrígan in “Musings on the Irish War Goddesses,” Nicole Bonivusto, ed. By Blood, Bone and Blade: A Tribute to the Morrigan Asheville, North Carolina: Bibliotheca Alexandrina, 2014, pg. 103.[viii] Proinsias Mac Cana mentions Scáthach briefly under the heading of “Goddesses of War” on page 86 of Celtic Mythology, NY: Peter Bedrick Books, 1987, yet refers to her as “supernatural” on page 102; Rosalind Clark. The Great Queens: Irish Goddesses from The Morrigan to Cathleen ni Houlihan, Savage, MD: Barnes and Nobel Books, 1991 pg. 28.[ix] Miranda Green, Celtic Goddesses: Warriors, Virgins and Mothers, New York: George Braziller, 1996, pg. 149; Nagy, The Wisdom of the Outlaw, pg.109-111.[x] Epstein, “War Goddess,” ch 2.

Copyright © 2014 Saigh Kym Lambert

The Morrígan and Cú Chulainn pt. 3: Of death and dog meat

If you find this article helpful, please remember this was work to put together and I have animals to feed and vet

When I did the first two sections of this “series” “On Saying ‘No’” and “Insult and Praise as Incitement” I only touched briefly on Cú Chulainn’s actual death, just to note that the two encounters discussed in those posts are not reason that the Morrígan killed him…as many claim She did. I had noted in the first part that She was not the Badb who brought about Cú Chulainn’s demise and in the second that he did not die during the Táin Bó Cúalnge and that Her “predictions” of such a death was actually to incite him. I had intended to discuss it further here, yet never finished, perhaps partially due to the loss of my own Cu, a Greyhound, shortly before starting this series and then the illness and loss of my other Greyhound. But as I again was asked about “if what you wrote was true, why did She kill him?” and, of course, “how can you worship a Goddess who would serve dog meat!?!?!?!?” I guess this is overdue.

I did note briefly in “Musings on the Irish War Goddesses,” that there is a confusion between the Morrígan and one or three Daughters of Cailitín, who CC had killed, and possibly even a third being, who might be the Morrígan or Badb or…not. (Lambert, pg. 119). PSV Lupus went into this issue a bit more in one of es essays in the same anthology (Lupus, pg. 36-38) as had both Angelique Gulermovich Epstein and Kim Heijda in their academic work (Gulermovich Epstein, Ch.2; Heijda, Ch. 4.2). However, as the alternative that it was the Morrígan/Badb who killed him is frequently repeated, I feel this needs to be as well. Especially as I do have a canine focus in my form of worship and service to the War Goddesses which makes the dog meat thing particularly negative if that were Her.

Which, of course, it wasn’t!

The problem seems to arise from the reasonable, as it happens several times in the texts (and as I discuss in “Musings,” pg. 103-105), conflation of the Morrígan and Badb combined with the not so realistic idea that “Badb” always means the Goddess who is one of the Daughters of Ernmas. The name, or title, might actually be held by many beings, sometimes in the plural, and might be intepreted as meaning something like “witch.” (Lambert, pg. 101; you could say Heijda’s entire thesis is about exploring the variations of this title). This notably includes one or three of the daughters of Calatín.

Calatín Dána and his 27 sons and a grandson fought and were killed by Cú Chulainn during the Táin Bó Cúalnge (TBC, pg.69-71, 209-211), his wife then gives birth two three sons and three daughters who in the end act to bring about CC’s death. (Hull, pg.235-263). It is his three daughters, one or all three called “Badb,” who offer Cú Chulainn the shoulder of a hound to eat, causing him to have to break either this geis against refusing food if he went near a cooking-hearth or the one against eating dog meat. Taking it causes the hand he ate from and the leg which he put the rest under to wither, making him vulnerable and weak.(Hull, pg. 254-255) It was, therefore, not the Morrígan at all who caused his death and certainly not She who gave him dog meat.

In fact, an Morrígan‘s actions in regards to Cú Chulainn’s coming death was quite the opposite. The night before he goes out to his last battle, the Morrígan damages his chariot, as She did not want him to go to battle for She knew he would not come back.(Hull, pg. 254) This is not the act of someone trying to destroy the hero, but instead trying to save him. Because She did not hate him, as this never dying modern belief attests, but loved him so. He was Her Hound!

In this story is also the Washer at the Ford, ingin Baidbi (Badb’s Daughter) who mourns his coming death.(Hull, pg. 247) Both Epstein and Heijda believe She is the Morrígan or Badb, as does Lupus. (Gulermovich Epstein, Ch.2; Heijda, Ch. 4.2; Lupus, pg. 37) I’m personally intrigued by the possibility that She is another family member, Badb’s actual daughter. However, this is largely a UPG thing to explore, with no way to truly know. Whether they are one and the same or relatives, it is clear that both the Morrígan and Badb’s Daughter did not wish Cú Chulainn dead, but at one point tried to stop it and in another lamented.

The crow that lands on Cú Chulainn’s shoulder is also not noted in the text to be the Morrígan; the clearest actual purpose in the tale is that a carrion bird landing indicates the hero is, indeed, dead. That it was the Goddess claimed by Hennessey, while Hull made a note that in one version it was Calatín’s daughter making sure CC was dead). (Hennessey, pg. 51-52; Hull pg. 160) Yet the term is ennach, not badb (Heijda, Ch. 5, Gulermovich Epstein, Ch.2). Lupus argues that there is no reason to interpret the crow as the Morrígan, while Epstein notes it’s a valid interpretation given their relationship and notes that in Rec. 3 of the TBC the Morrígan is said to take the form of an ennach. (Lupus, pg. 36-37; Gulermovich Epstein, Ch.2). Heijda’s take is that it is clearly not the Goddess Badb, probably not the Morrígan (she is a bit more convinced of Them being different than most), is may be Catalín’s daughter as Hull notes, as the daughter had appeared as a bird previously. (Heijda, Ch 5)

Myself, I still tend to agree with Gulermovich Epstein on it being the Morrígan. While to some extent this is from Gulermovich Epstein’s arguments, I admit it is also a bit UPG. It makes sense that the Goddess, as his patron as I feel the evidence indicates She is, would be with him at the end. Not to celebrate or gloat as some claim, or as the daughter of Catalín would, but to mourn, to perhaps protect him. This would mean, of course, that perhaps one thing She said in the Táin Bó Regamna truthful, but meant differently than it might seem in the context of that tale, “I am guarding your death, and will continue.”

See also: The Morrígan and Cú Chulainn: On Saying “No”

The Morrígan and Cú Chulainn pt. 2: Insult and Praise as Incitement

Bibliography

Saigh Kym Lambert, “Musings on the Irish War Goddesses,” By Blood, Bone and Blade: A Tribute to the Morrígan Nicole Bonivusto, ed, Ashville, NC: Bibliotheca Alexandrina, 2014

A. H. Leahy, ed. and trans, “Táin Bó Regamna,” Heroic Romances of Ireland, Volume II London: David Nutt, 1906 Irish English

P. Sufenas Virius Lupus, “The Morrígan and Cú Chulainn: A More Nuanced View of Their Relationship,” By Blood, Bone and Blade: A Tribute to the Morrígan Nicole Bonivusto, ed, Ashville, NC: Bibliotheca Alexandrina, 2014

Cecile O’Rahilly, trans., Táin Bó Cúalnge from Book of Leinster Dublin: Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, 1967 Irish English

Copyright © 2014 Saigh Kym Lambert

The Morrígan and Cú Chulainn pt. 2: Insult and Praise as Incitement

If you find this article helpful, please remember this was work to put together and I have animals to feed and vet

|

| “Cuchullain and the Battle-Goddess”

by Willy Pogány in The Frenzied Prince based on Táin Bó Regamna

|

In my earlier post about an Morrígan appearing to Cú Chulainn and offering sex and victory as a test, I noted that this is not featured in all versions of the Táin Bó Cúailnge. Instead, the Book of Leinster edition uses the remscéla (foretale) Táin Bó Regamna, to set up Her coming at him as a heifer, eel and wolf.(TBC pg. 54, 194) The story is, again, read as if showing their hatred of each other and why CC needs to be “punished.” There are several other issues which come up with it, however, which again make no sense if you read it this way and also view the Morrígan as a powerful Goddess.

The Táin Bó Regamna is one of the stories which sets up the circumstances for the Táin Bó Cúailnge, in which the Morrígan essentially sets the entire stream which makes sure Cú Chulainn will play his role. She steals a cow to breed to the Donn Cúailnge, the bull Medb will raid for. Cú Chulainn tries to stop the theft, finding Her all in red in a chariot with a single red, one legged horse with the pole running through it and a man herding the cow. He is first angered that the “woman” answers rather than the man, he even leaps upon Her shoulders. She identifies Herself this time as a satirist, which should at least be a clue as to the words She then gives. The chariot, horse, man and semblance of a woman disappear and She takes the form of a black bird, revealing who She actually is. She seemingly predicts that he will die in a cattle raid when the calf the cow carries is a year old. This gets him angry and he boasts that he will not only survive the raid but will kill all who come against him and will find his fame in it. She then makes the threat of coming against him as eel, wolf and heifer while he counters as to how he will wound Her. She disappears with the cow.

Now it’s often said that in this She is speaking prophecy, yet if we believe She is a powerful Goddess with great prophetic powers, how can this be? She would be, after all, wrong for, as he proclaimed, he didn’t die then. Even a true satire, one meant to create magic which makes the words so, would mean he’d have to die in the TBC…or it means She has little power. So again, we see that if this is taken as it usually is, that they are truly contentious, it shows Her as weak. Perhaps not a problem for some focused on him, but as a follower of Her it is problematic.

So, again, let’s consider what else this might be. What I believe it is is gressacht. This is a form of incitment to battle, using mocking and insult to create rage in the fighter, related to the laíded which Mac Cana demonstrates is incitement through praise.(MacCana, pg 77-78) He notes the War Goddess doing this in his Macgnímrada which is part of the TBC, and that it is obvious what She is doing there despite the term not being used. (MacCana pg. 80) Therefore seeing this in the TBR as well as part of the exchange between them in the TBC which we have discussed, shows a pattern, one fitting the role of a warrior and the Goddess who would wish to incite him.

She is, of course, not the only one using this form of incitement on him nor is he the only one it’s used on. In fact, in his battle with Lóch, when She also attacks him, this form of incitement is used on both of them. The women of Connacht and then Medb taunt Lóch to get him to fight Cú Chulainn. Seeing CC in trouble fighting both the eel-shaped Morrígan and Lóch, Fergus called upon one of the Ulstermen to incite him so that he can defeat them both and Bricriu steps up to the task. (MacCana, pg. 79). But perhaps the best known example is when Cú Chulainn must face his beloved Ferdiad and he asks his charioteer Láeg to incite him in this way. (MacCana, pg. 77-78)

The response, to gressacht is expected to be “I’ll show you!” But wordier then followed with the action. Again, we see exactly this in the paring of the TBR interaction between Cú Chulainn and an Morrígan and the events in the TBC.

The concept of the inciting the warrior into action by verbal insult is hardly unique to early Ireland. Most of us know of the verbal lashing associated with drill sergeants and coaches. The idea, especially in the military, had been to create soldiers who could take pressure. And resist being female, as it’s commonly the featured insult (interestingly, MacCana noted that the Irish insults never use the accusation of being womanly to insult men, pg. 90-91 although I think we might want to look at how it was still used as in insult regarding Medb). However, in light of awareness of bullying’s devastating consequences these methods have been questioned and curbed, although some surely still practice them when possible. We have seen it seep into pop culture “fitness” thanks to Jillian Michaels. In fact, some personal trainers call such abusive tactics “going Jillian Michaels on someone” and, yes, this is considered a very inappropriate way to treat a client.. Because the problem is that uch insulting usually is nothing more than verbal abuse. Bullying. Because for all some might claim it’s for “their own good” it’s really about control. And it’s done without regard for what baggage the person it’s being said to already has.

If someone has grown up with verbal abuse, they have learned from the beginning to not respond positively. They have been taught that “I’ll show you!” is not the sought after response. More of abuse just causes more pain and damage, even if the abuser expects and wants a “I’ll show you!” response. And that’s something we must always be aware of. I am not calling for us to use this as a method….unless the person on the receiving end requests it, like CC asked his charioteer. Not even among my, ahem, cult members, although I think this concept has a place as we’ll get to. In fact, MacCana notes that only certain people seem to have been allowed. Charioteers, women (and there is a heterosexual component with the recipients being male), satirists….Fergus cannot do it, so he calls up on those who can (MacCana pg. 86-89). Obviously, Goddesses would be among those who can.

The fact that verbal insult can demoralize, psych out, rather than provoke, psych up, was also evident in the Irish literature and in sports today. MacCana notes the various times when screams, shouts, taunts and other noise is mentioned in the war literature, either from opposing forces or the War Goddesses.(MacCana, pg. 69-74) This too is used in modern sports, especially seen in fighting sports (and taken to a crazier level in scripted “wrestling”). But we can often see that sometimes it does psych up rather than psych out, as taunts are thrown and countered with “I’ll show you!” (sometimes both almost as poetic as in the literature). Of course, a fighter might want to have their opponent visibly psyched up, it makes for a more glorious fight. We have hardly left the idea that we discussed earlier that a good fighter wants to be known for having a good fight, not an easy win.

As part of that, of course, we again have the laíded, the praise. Not just given by the supporters of the winner or the loser of the winner (part of “good sportsmanship” and “losing well” is to be sure that now everyone knows you lost to someone who was very good, that your skills will benefit from this and “I’ll show you next time!”) but often the winner of the loser. There is no glory in making out the opponent you beat as having no skill, the more skilled they are the more you must have been. We insult, then we praise.

How can we use this today? As I said I think with care, for harming those harmed already is useless. And some of my suggestions are not likely going to sit well with those who might have such backgrounds. I want to say that I think learning to be able to say “I’ll show you!” is a good thing, but I also am well aware that my knowledge of the psychology of it all is far to limited to say how. I think it might be something some may wish to explore with professional help. It’s not something I’m familiar with because the forms of verbal abuse I can identify being an issue for me have been different…it’s been the “friendly, helpful,” sneaky, manipulative backhanded compliment type that “friends” taught me later in life. The overt, insult stuff I learned to blow off as a kid. Not always a “I’ll show you!” but more the belief my mother engendered that people who talked shit about you weren’t people who mattered.

Yet, even those who haven’t been overwhelmed by others’ abusing us sometimes do it to ourselves all the same. And maybe those backhanded compliments which slowly, subtly degrade our self-esteem at the hands of friends have their own way too. So even without the overt abuse, we feel we’re not smart enough, not strong enough, not skilled enough….. And we tell ourselves this.

So it’s the self-talk we may need to first learn to say “I’ll show you!” to. Say it with conviction and say it in poetic detail! And take the action to prove those voices wrong. Get creative with your response to the negative self-talk, hells, have fun with it! Because the way to deal with it from others is to first deal with it in yourself.

Again, this may well be a gross oversimplification for many, so if you’re not do not let that strengthen the bad self-talk instead! Please! There are also times to be gentle with yourself.

And to praise yourself! Never forget that side of it!

I do think there is room, for some, for doing this between two people. There are even situations where some might seek it out. I have realized one for me, something which …well…is a bit odd.

Although my father never insulted my ability with horses that I can remember, I developed at an early age a need to prove myself to him. Perhaps this was actually a response to a sense of protectiveness that the feminist child I was resented? In more recent years I know my father was quite worried about, first, the crazy abuse survivor, Saoradh, I rescued and, later, my crazy filly, Saorsa, but I was determined to show him in both cases. I did with Saoradh who became calm, happy and no longer so violently reactive in his last years. But when he died, I seemed to internalize the worry. I became afraid both of “ruining” her and of getting hurt. I became less self-confident with a horse than I have ever been and I ended up seeking a trainer to work with her. And despite that, I just wasn’t getting ti back. I was getting a great deal of encouragement from my mate and from the trainer…but I couldn’t find it in me.

Then we had a farrier here who flat out told me she was too much horse for me, she’d make a great horse for someone who was confident and I should sell her. And it was like a fucking light switch went off. After that I began working with her myself and progressed greatly. Sadly, when he nearly crippled our other mare we had to find another trimmer and I no longer have his reminder to keep that up. What I do have is a husband confused at why I get annoyed with my doubts come back and he tells me I can do it. Apparently horses are one area where I need someone who makes me say “I’ll show you!” even if they’re not actually taunting me. (maybe someone will read this and take on the role LOL)

Having identified this one place where I seem to need someone to prove myself to, I can see where that need can be used to strengthen myself. I could see a place for ritualized taunting among warriors. I can also feel that the War Goddesses do do this to us, even today. That perhaps “self talk” isn’t…but then don’t we believers often struggle with who might actually be speaking in our heads (and the accusations non-believers might have on that)? And that, really, it might work best as the taunter is on your side, as Bricriu, Láeg and, most assuredly, the Morrígan really were on Cú Chulainn’s. That such interaction is not adversity but aid. That those taunting know, as does the recipient, that the taunts are lies. And that they’ll be there to praise after. But, sometimes, you have to settle for a know it all asshole who can’t even do his own job adequately.

I do know that there are times when a small murder of crows in a tree I’m going buy when I’m just not feeling into a run feels like more than just a group of wild birds squawking at each other, but are aiming gressacht their remarks at me. I know because it brings up the “I’ll show you!” feeling in me. And I know the difference in the run before and after. And I know the feeling when I put a bit more effort in a run and a chorus of coywolves erupts just as it’s coming to an end, that more than just a local pack calling for a hunt, it’s laíded for my effort. Small moments, but we can find strength in the face of insult and we will feel rewarded. We just have to remember, sometimes the One who taunts will give the deepest praise once we show Her.

See also:

The Morrígan and Cú Chulainn: On Saying “No”

The Morrígan and Cú Chulainn pt. 3: Of death and dog meat

I also discuss some of this, as well as expand on the nature of the Morrígan “Musings on the Irish War Goddesses” in By Blood, Bone and Blade: A Tribute to the Morrígan Nicole Bonivusto, ed, Ashville, NC: Bibliotheca Alexandrina, 2014

Bibliography

A. H. Leahy, ed. and trans, “Táin Bó Regamna,” Heroic Romances of Ireland, Volume II London: David Nutt, 1906 Irish English

Proinsias MacCana, “Láided, Gressacht ‘Formalized Incitement’” Érui vol. 43

Cecile O’Rahilly, trans., Táin Bó Cúalnge from Book of Leinster Dublin: Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, 1967 Irish English

Cecile O’Rahilly, trans. Táin Bó Cúalnge, Recession 1 Dublin: Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, 1976 Irish English

Copyright © 2013 Saigh Kym Lambert

The Morrígan and Cú Chulainn Part 1: On Saying “No”

If you find this article helpful, please remember this was work to put together and I have animals to feed and vet

Those of us who follow an Morrígan are in an interesting position compared to many Gaelic Polytheists. We actually have an example of a patron/client relationship between a Deity and a human (albeit a human with divine paternity, sort of). It is, of course, through Christian eyes that we get it, so many dismiss this all together. This is particularly true as this warrior, Cú Chulainn, often offends the sensibilities of many who claim to be devoted to Her and on the warrior path.

There are many issues, really, but right now I want to concentrate on aspects of the relationship between CC and the Morrígan which I feel are widely misunderstood. The problem is that without looking at some of the issues from a warrior perspective, including by people who claim to be warriors, and with an understanding of certain elements of Irish culture, it can be read in a very different way from what it may have meant to early warriors who may have heard and orally shared the stories. Some of the scribes who wrote them down, also not being warriors, may well have considered them much as we do today, yet the actual stories seem to give a different read when taken from a warrior perspective.

The reading that many in the Pagan community, from the “fluffiest of fluffies” to the “hardest core Reconstructionists,” give the relationship is that CC is rude, arrogant and offensive to the Morrígan. And it can appear so. Even form the earliest encounters as a boy, when She mocks him as unable to fight a phantom, which he then does defeat.(TBC Rec I, pg. 16, 139) It seems there that She doesn’t like him much, but consider then what that means that CC actually orders his charioteer to mock him at a later point.(TBC Rec I, pg. 93, 207) At some point I hope to further explore gressacht, inciting by ridicule, something which is very difficult to understand in a culture where it would be mistaken for bullying which is meant to crush us.(MacCana)

The biggest confusion comes from his response to Her in Táin Bó Cúailnge Rec I, when she comes to him and offers him Sex in the middle of his standoff at the ford. This tale actually does not appear in all of the versions of the TBC and I hope to explore the events in the Táin Bó Regamna (Edit: and I did in Part 2) which also serves to set up the same events at a later time. (I have explored both somewhat already in, “Musings on the Irish War Goddesses” publication pending) Both of these do, after all, seem to get heavily misread.

The reading of this version is that he spurns Her offer of “love” and She, being female and therefore only able to resort to revenge when crushed in this way, punishes him by coming against him while he’s in battle. Some of these retellings of the meeting between CC and the Morrígan make Her out to be a truly pathetic woman we are supposed to feel sorry for while others point what a mistake it is to refuse such a powerful Goddess…some manage to take both these directions at once. It is used by several “warriors” to show why one does not refuse the demands of the Goddess, ever (in what appears to be an attempt to excuse their own recent actions).

This is a translation of the exchange in question:

Cú Chulainn saw coming towards him a young woman of surpassing beauty, clad in clothes of many colours. ‘Who are you?’ asked Cú Chulainn. ‘I am the daughter of Búan the king,’ said she. ‘I have come to you for I fell in love with you on hearing your fame, and I have brought with me my treasures and my cattle.’

‘It is not a good time at which you have come to us, that is, our condition is ill, we are starving (?). So it is not easy for me to meet a woman while I am in this strife.’ ‘I shall help you in it.’ ‘It is not for a woman’s body that I have come.’

‘It will be worse for you’, said she, ‘when I go against you as you are fighting your enemies. I shall go in the form of an eel under your feet in the ford so that you shall fall.’ ‘I prefer that to the king’s daughter,’ said he. ‘I shall seize you between my toes so that your ribs are crushed and you shall suffer that blemish until you get a judgment blessing.’ ‘I shall drive the cattle over the ford to you while I am in the form of a grey she-wolf.’ ‘I shall throw a stone at you from my sling so and smash your eye in your head, and you shall suffer from that blemish until you get a judgment blessing.’ ‘I shall come to you in the guise of a hornless red heifer in front of the cattle and they will rush upon you at many fords and pools yet you will not see me in front of you.’ ‘I shall cast a stone at you,’ said he, ‘so that your legs will break under you, and you shall suffer thus until you get a judgment blessing.’ Whereupon she left him (Cecile O’Rahilly, trans. Táin Bó Cúalnge, Recession 1 Dublin: Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, 1976 English pg. 177, Irish pg. 37)

At face value, taken as a modern story, the reading given does seem obvious. It appears She comes in disguise, however, even in doing so Her role is very clear. Epstein notes that She clearly reveals Herself as a Sovereignty/Victory Goddess when She offers help in his battle. (Epstein, sorry due to mangled formatting I have no page number) Yet there seems at least some hint in calling Herself the daughter of King Búan. A king’s daughter to make a king, Búan linked to “Búanann” a name related to Anann and therefore the Morrígan.(O’Donavan, pg. 17, Epstein) She does indeed say She loves him…for his fame. Which many others did as well, but given context, it could serve as a reminder that, indeed, the glory he has sought since childhood is why She is there.

Certainly, She does say, “It will be worse for you when I go against you as you are fighting your enemies.” So that must mean She’s angry and is going to retaliate. Right? Say “no” to this Goddess is a foolish thing. Because Cú Chulainn’s life was horrible and hard and we’d never want what he had. Wait? What?

No, let’s look at what is She really offering and what is he rejecting? She is saying She is offering love and, obviously, sex. Yet even those mistaking this for a story of scorn love realize that this is also about offering victory as She offered Dagda in the Cath Maige Tuired. (CMT, para. 84) Of course, many seem to think of that as a love story as well, rather than the powerful rite that it was. Dagda accepts and while the victory is not easy, it is had. Cú Chulainn refuses, the Morrígan is hurt and refuses him victory and he is destr…..oh, wait.

I realize this may be really hard for people to grasp. But Cú Chulainn does win. But it’s not easy. And She does make it harder. But was that punishment? Really?

Let’s compare what is different about CC and Dagda for a moment. Dagda is a God, an equal in all ways to the Morrígan. He is an established warrior among the Tuatha Dé Danann and has even been king. He has His own magic, again well established. Mostly, He has nothing to prove.

Cú Chulainn as a boy took up arms when he heard it was a good hour to do so to live a glorious life and die

|

| The boy Cú Chulainn by Stephen Reid 1912 |

young and famous. He had by this time proven himself many times yet was always challenged for his youth and strangeness. He was still a youth and this was, in fact, the story which would make that fame if he was to have it. While other exploits contributed, this was the story which marked him. He still had to fight it.

So let us think what the Morrígan was doing here, actually doing here.

Let’s think that all evidence we have. She does love him.. If we try to understand the gressacht for what it is and we realize that at his death She is distraught and is not Cailitín’s daughter who is also, confusingly, called Badb, who facilitates his death. Rather She tries, despite obviously knowing it’s futile to prevent it. (Van Hamel, pg. 69-133, O’Grady and Stokes in Hull, pg. 235-263) this becomes clear. And She does love him for his fame or rather his determination to have it. And that is important.

What she is offering, by offering him to lie with Sovereignty/Victory, is to lose that all. Think. Go beyond what you think is good or bad, is reward or punishment and think what he had wanted. And think what laying with Victory would give.

What she offered was an easy victory during the events which would mark his fame. He clearly knew who She was and what that would mean. He would have won easily, there would be no tale to tell, he would have been at best a side note but possibly totally forgotten. We’d have no stories today.

ETA: I should also note, that She’d have turned from him, as well. He’d be forgotten for he’d never do anything of note. He’d be no champion and his people would be left without.

This is called a test. She did not want him to say “yes.” If he had then he’d undoubtedly have been punished. He’d have won easily and been forgotten. The worse punishment there could have been for him.

The punishment you see, that She comes against him while he is in battle, serves to further his fame. A fight that is “worse” means winning is better. For he not only faced a warrior but the War Goddess in battle. Do you really believe that She is so weak he would have won against Her if that wasn’t the point? Then why worship such a weak Goddess?

That, btw, is something that boggles me. Especially, among those who then claim “well, She showed him not to say “no” to her!” Um, he won. Is this the extent of strength you see in your Goddess? That She’d try to fight him for real and failed? Then you claim you are afraid to say “no” to Her? What sort of wimp are you then?

Instead, I believe She acts to show Her chosen favorite is indeed mighty! Rather than an easy and easily forgotten victory, She gives him a harder one, one that let’s him rise above all! Because he knew to say “no” to Her test.

She then offers him milk, again in “disguise” which must clearly have been evident. A three teated cow in the presence of an old woman doesn’t add up to a Goddess of cattle? In this She gives him fame for the other side of war, that he also can heal, even a Goddess.

Think. What is punishment to a warrior who as a very small child declared he wanted to have a glorious, famous short life? Why, it would be to have forgotten long one.

And if one thinks a forgotten life is better if you live safely into old age, are you ready to walk the warrior path? None of us are Cú Chulainn, but if you choose a safe life and easy victories, if you choose to say “yes” when ever She tests you to see how much you want what you claim you want then you are far from following his way.

This is a lesson we must learn, that She will ask of us things that go against what we know deep down in our hearts is the right way. She will ask us to do things which She does not want us to do. To serve the Morrígan one needs to have the courage to say “no.” While there are many ways that Cú Chulainn might be a problematic role model, showing the importance of passing such tests is not one of them. He shows us well. Act in accordance to your heart when the Phantom Queen tests you and it will serve you well. Even if the weak can never understand.

See also:

The Morrígan and Cú Chulainn pt. 2: Insult and Praise as Incitement

The Morrígan and Cú Chulainn pt. 3: Of death and dog meat

I also discuss some of this, as well as expand on the nature of the Morrígan “Musings on the Irish War Goddesses” in By Blood, Bone and Blade: A Tribute to the Morrígan Nicole Bonivusto, ed, Ashville, NC: Bibliotheca Alexandrina, 2014

Bibliography

Angelique Gulermovich Epstein, “War Goddess: The Morrígan and her Germano-Celtic Counterparts” dissertation, University of California in Los Angeles, 1998

Elizabeth Gray, trans. Cath Maige Tuired: The Second Battle of Mag Tuired Dublin: Irish Text Society, Irish English

Eleanor Hull, ed., The Cuchullin Saga in Irish Literature: being a collection of stories relating to the Hero Cuchullin, London: David Nutt on the Strand, 1898 (Hayes O’Grady, trans., “The Great Defeat on the Plain of Muirthemne before Cuchullin’s Death” and Whitley Stokes, trans., “The Tragical Death of Cochulainn,)

Proinsias MacCana, “Láided, Gressacht ‘Formalized Incitement’” Érui vol. 43

Kuno Meyer, trans. ‘The Wooing of Emer’“Tochmarc Emire,” Archaeological Review 1, 1888, Irish English

John O’Donovan, ed. and trans. (with notes and translations from Whitley Stokes) Sanas Cormaic Calcutta: O. T. Cutter for the Irish Archeological and Celtic Society, 1868,

Cecile O’Rahilly, trans. Táin Bó Cúalnge, Recession 1 Dublin: Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, 1976 Irish English

AG van Hamel Compert Con Culainn and Other Stories, Medieval and Modern Irish Series, Vol 3, Dublin: Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, 1933

Copyright © 2013 Saigh Kym Lambert