In a previous post I noted the idea of finding inspiration in the stories of ancient Gaelic ban-fhénnid and indeed you can find many tales online and in books retelling and extrapolating these stories to be more positive than they may have been. One issue, of course, is that not all of these retellings are labeled as such, this is especially true, it seems, within the NeoPagan community but a second source tends to be tourist literature. There are many out there who think they know more about Scáthach or Medb than is really in the texts, which if given the label Unsubstantiated Personal Gnosis is fine, but at least in the non-Pagan sources UPG certainly isn’t a factor. There is, btw, quite a great deal on Medb in the text that is not so widely shared, while Scáthach actually has far less material on her. (Diana Veronica Dominguez, Historical Residues in the Old Irish Legends of Queen Medb: An Expanded Interpretation of the Ulster Cycle, Lewiston, NY: Edwin Mellen Press, 2010 is an excellent study of Medb using tales often not bothered with, making her far more human and far less a joke than what is usually focused on)

I believe one of the keys to using these stories wisely, is to be very clear about the fact we are making changes to them. Again looking at Medb, especially as examined by Dominquez, we can retell her story through what we as women can imagine are her eyes, rather than of the male eye which may use the tale to mock a woman making war. We can also emphasize things that some scholars choose to ignore in retelling her story. In order to point out that her quest for the bull in the Táin Bó Cúalnge is the folly of a haughty woman, it’s often left out that she, in fact, also had a reasonable quest for revenge against her former husband Conchobar, who had raped her and killed her son . Medb’s story really has a lot to offer in retelling without actually changing much or adding anything. Yet in retelling it we must be clear that it’s a different perspective from the way the Ulster Tales came down to us, possibly a different perspective than it was viewed by anyone before.

Scáthach, and most of the other warrior women in the texts, we really don’t have much on. It’s in this that we see that while there may be many female warrior names banted about, their stories are very much peripheral to the stories of male warriors, saints or they died horribly in place-name tales. If we tell more of her story than what is in the texts, we likewise need to be clear. For many of us these tellings might be UPG,even SPG (Shared Personal Gnosis), but to those who don’t believe, or simply don’t believe your UPG, stories from such sources are merely modern fictions. I believe it’s okay to have them, we just must be clear that these are not from the source.

Even Macha Mong Ruadh, whose story as a warrior queen is short but quite detailed and positive for her, I believe (although, you know, everyone dies at some point in every tale), offer’s caution. When we tell the tale we might be clear that when she lures the brothers one-by-one into the forest she overtakes them by her own hand. But it’s not actually told what happens in those woods. Someone who does not see women as capable of overpowering men, oh what sheltered lives they must lead, might be thinking she used magic, the only power many think women can ever have, especially those who don’t believe in magic, or had warriors waiting even if this version notes that she bound them.

So, yes, we can retell, we can extrapolate, but we must be clear that’s what we’re doing. And I think we also must take care not to go too far. After all, if a story is of a woman who is clearly not a fighter, why make her so when there are those who are? If we’re going to totally create a new character, should we give her a name of one that is the opposite of what she is. And while we might do this in fiction, non-fiction commentary on literature and history should be way out.

The most stunning example of completely changing the story of a woman in the texts, and not revealing that it is a modern fiction and not what is in the texts, is not actualy from either NeoPagan or a tourism agency, it’s from academic and novelist Peter Berresford Ellis.

I think he was even stretching it to describe Erni (aka Erne for whom  Lough Erne was named) as Medb’s warrior his “Peter Tremayne” novel Badger’s Moon (Sister Fidelma #13, NY: St. Martin’s Press, 2005), however, he lists her as such also in Celtic Women: Women in Celtic Society and Literature (Grand Rapids, Michigan: Wm.B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1996 pg. 73). This is now happily repeated by countless NeoPagan websites and by Jessica Amanda Salmonson in The Encyclopedia of Amazons: Women Warriors from Antiquity to the Modern Era (University of Michigan, Pagagon Press, 1991). Admittedly, her work is full of poorly substantiated entries, with fiction and historical women noted as equally valid, but in this case she might be forgiven, for scholar Ellis says Erni is a mighty warrior, so we should admire her great deeds. Mighty is Erni!

Lough Erne was named) as Medb’s warrior his “Peter Tremayne” novel Badger’s Moon (Sister Fidelma #13, NY: St. Martin’s Press, 2005), however, he lists her as such also in Celtic Women: Women in Celtic Society and Literature (Grand Rapids, Michigan: Wm.B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1996 pg. 73). This is now happily repeated by countless NeoPagan websites and by Jessica Amanda Salmonson in The Encyclopedia of Amazons: Women Warriors from Antiquity to the Modern Era (University of Michigan, Pagagon Press, 1991). Admittedly, her work is full of poorly substantiated entries, with fiction and historical women noted as equally valid, but in this case she might be forgiven, for scholar Ellis says Erni is a mighty warrior, so we should admire her great deeds. Mighty is Erni!

Um…..

Before recounting, with citation, Erni’s great deeds, I’m going to be perfectly honest, Ellis obviously has better resources than I do, so maybe there’s some lost tale about Erne (yeah, I keep changing the last letter, “e” seems more common, he uses “i” and we’re discussing his work so, I’m trying to use “i” when referring to his work) that indicates this, that is totally opposite the versions I could find. If so, I shall happily stand corrected and rejoice in the finding of another warrior woman. The problem is, Ellis doesn’t cite his sources (bad academic, no biscuit!).

Here are her deeds, the bold emphasis is mine, the italics are not but rather indicate a mistranslation noted on the website source, see note next to it:

13. The chaste Erne, who knew no art of wounding,

50] the daughter of loud-shouting Borg Bán

(the warrior was an overmatch for a powerful third)

the white-skinned son of Mainchin son of Mochu.

14. The noble Erne, devoid of martial spirit, (footnote here notes correct translation is ‘free from venom’)

was chief among the maidens

in Rath Cruachan, home of lightsome sports:

women not a few obeyed her will.

15. To her belonged, to judge of them,

the trinkets of Medb, famed for combats,

her comb, her casket unsurpassed,

60] with her fillet of red gold.

16. There came to thick-wooded Cruachu Olcai

with grim and dreadful fame,

and he shook his beard at the host,

the sullen and fiery savage.

17. 65] The young women and maidens

scattered throughout Cruach Cera

at the apparition of his grisly shape

and the roughness of his brawling voice.

18. Erne fled, with a troop of women,

70] under Loch Erne, that is never dull,

and over them poured its flood northward and

drowned them all together.

The Metrical Dindshenchas, English: The Irish

That the more accurate translation is “free from venom” is actually interesting, given this would say that she’s not only not a warrior, but also harmless “even for a woman.” Poison being commonly considered a “woman’s weapon” by those who have throughout history seen us incapable of actual confrontational violence.

For comparison, the The Edinburgh Dinnshenchas tells the same tale and includes:

Erne with pride, a pure union,

Daughter of good Borg the Bellowing,

She fled — no deed to boast of —

Under Lough Erne for exceeding fear.

The Edinburgh Dinnshenchas, Whitley Stokes, ed. and trans., Folklore 4 (1893) pg. 476, English The Irish pg. 476

The Dinnshenchas of Dubthar, from the Book of Lecan, offers other versions, again with much fleeing and concern with chastity the “insult to the honour of her noble father.” The Irish manuscript series, Vol. 1, Part 1, pg. 186-189

None of these show much warrior tendency, is there a version that does? If so, I’d love to see it and also know what period it is from. Are these the changes from an earlier warrior tale? Sadly, I’m very doubtful that any such tale exists.

Understand, that I see no shame in a woman who is not a warrior to run from a potential rapist. In fact, in most cases, I recommend running to non-professional warrior women, usually after disabling the guy in some way to increase your odds and make him easier for the authorities to catch. However, such mannerisms do not speak of a mighty warrior, a professional warrior according to Ellis, a warrior to a warrior queen. I do not understand why he’d claim she was. So maybe there’s a tale I can’t find?

I think as we tell ourselves stories from the past in ways that are more empowering to us than may have been intended by the original tellers, that we avoid going this far. And avoid making out that a woman in the story is something quite opposite of what she is. I don’t really understand what motivation Ellis might have had in calling Erne a warrior, I’m sure he’s seen all versions of this (and maybe another). But while we might want to find more warriors in the ancient stories, we need to look harder and not change the tales completely.

Text copyright © 2011 Kym Lambert

Photo of Lough Erne from Department of the Environment (DOE) Northern Ireland Environment Agency (NIEA) used under terms of Open Government License.

stuff. But the truth is, I can’t really remember how much of an influence she might have really been. It seems a lot, but I also realize some issues with those memories. Did I discover Greek Mythology or WW first?I don’t know. Did I gravitate to Greek polytheism when about 9 or 10 years old due to WW or was I drawn to her due to my devotion to Artemis? I don’t remember which came first.

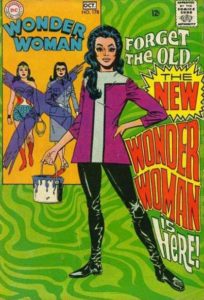

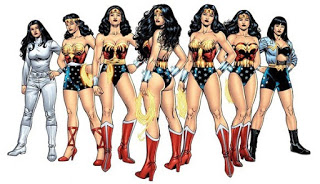

stuff. But the truth is, I can’t really remember how much of an influence she might have really been. It seems a lot, but I also realize some issues with those memories. Did I discover Greek Mythology or WW first?I don’t know. Did I gravitate to Greek polytheism when about 9 or 10 years old due to WW or was I drawn to her due to my devotion to Artemis? I don’t remember which came first. the blather on the web about it, she’s been on my mind. Oh, and that blather several months ago about her new costume in the comic, which most people talking about the new TV movie one, mostly, don’t seem to know about. Frankly, the costume even before the recent discovery I made wasn’t the biggest deal. Stupid but not the biggest deal. But then, when I started reading her book (and it was always sporadic that I got them), she shortly there after wasn’t wearing the Iconic Strapless Bathing Suit anyway. The Amazons had left Earth to save their powers, but Diana Prince stayed behind, gave up her powers and the Wonder Woman moniker, took up karate and opened a boutique. In some of the issues at the time, she wore a white jumpsuit, with flat soled boots, no less! So get over “she’s in pants, ZOMG!” she’s worn them before.

the blather on the web about it, she’s been on my mind. Oh, and that blather several months ago about her new costume in the comic, which most people talking about the new TV movie one, mostly, don’t seem to know about. Frankly, the costume even before the recent discovery I made wasn’t the biggest deal. Stupid but not the biggest deal. But then, when I started reading her book (and it was always sporadic that I got them), she shortly there after wasn’t wearing the Iconic Strapless Bathing Suit anyway. The Amazons had left Earth to save their powers, but Diana Prince stayed behind, gave up her powers and the Wonder Woman moniker, took up karate and opened a boutique. In some of the issues at the time, she wore a white jumpsuit, with flat soled boots, no less! So get over “she’s in pants, ZOMG!” she’s worn them before. (which is my real hair color, although I hennaed most of my adult life, I’m black to the blond now). And she wore a skirt, with dark tights and blue boots. And was played by Cathy Lee Crosby. I don’t really remember it much, but I remember being thrilled by the movie. I’m told it was actually very, very bad, but, hey, I was 12 and desperately looking for any good female character to watch. Even if it wasn’t a very good show…after all, TV was not particularly good back then, anyway. And I remember desperately wanting a blond Goddess worshiping, ass kicking role model. (yeah, I know, poor little ‘underrepreseneted” white girl, hey, I was a kid)

(which is my real hair color, although I hennaed most of my adult life, I’m black to the blond now). And she wore a skirt, with dark tights and blue boots. And was played by Cathy Lee Crosby. I don’t really remember it much, but I remember being thrilled by the movie. I’m told it was actually very, very bad, but, hey, I was 12 and desperately looking for any good female character to watch. Even if it wasn’t a very good show…after all, TV was not particularly good back then, anyway. And I remember desperately wanting a blond Goddess worshiping, ass kicking role model. (yeah, I know, poor little ‘underrepreseneted” white girl, hey, I was a kid)

all of it here. That’s been done anyway by Carol A. Strickland at

all of it here. That’s been done anyway by Carol A. Strickland at  This is the original suit. Note, no red boots, although they were there in the beginning once she was actually in the comics. The strappy sandals, hmmm…just another nod, such as the lasso and cuffs, to Marston’s bondage lifestyle? Keep the straps in mind, now, we’ll come back to that later. (However rather than diverge into Marston’s lifestyle, including living with two women and believing that bondage would bring world piece, I will let SheWire.com speak in

This is the original suit. Note, no red boots, although they were there in the beginning once she was actually in the comics. The strappy sandals, hmmm…just another nod, such as the lasso and cuffs, to Marston’s bondage lifestyle? Keep the straps in mind, now, we’ll come back to that later. (However rather than diverge into Marston’s lifestyle, including living with two women and believing that bondage would bring world piece, I will let SheWire.com speak in

up instead) and short lives once they donned the Iconic Strapless Bathing Suit. Hippolyta, Diana’s mother, took the role, her adopted sister Donna Troy who had become Wonder Girl took the Wonder Woman moniker in a somewhat more metallic costume.

up instead) and short lives once they donned the Iconic Strapless Bathing Suit. Hippolyta, Diana’s mother, took the role, her adopted sister Donna Troy who had become Wonder Girl took the Wonder Woman moniker in a somewhat more metallic costume.

he arms. However, the jacket comes off.

he arms. However, the jacket comes off.

No clue as to the third, can’t find it anywhere. Nope, not going to give DC money to find out.

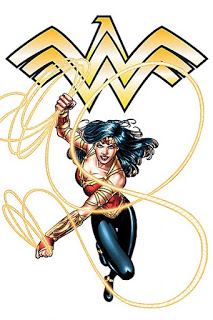

No clue as to the third, can’t find it anywhere. Nope, not going to give DC money to find out. some of the feed back out there got picked up. Red boots, why that was such a big deal is beyond me, but I do approve of the lower heel. Slightly darker, less shiny legging with stars, the last was another thing that really wasn’t a big deal to me. But the strapless top, waaay too low to be remotely reasonable, just is so bad. In the

some of the feed back out there got picked up. Red boots, why that was such a big deal is beyond me, but I do approve of the lower heel. Slightly darker, less shiny legging with stars, the last was another thing that really wasn’t a big deal to me. But the strapless top, waaay too low to be remotely reasonable, just is so bad. In the  As I wasn’t writing much about Gaelic spirituality at the time I started this blog, having started at a time of conflict, flux and burn out in the community and taking things more private for awhile, I have realized it might seem a sudden switch to some of my readers. While the intent of this was always to be about various aspects of the warrior path in my life and how they came together, the focus had been on fitness, self-defense and popular culture. That itself might seem quite a mix to some. But it really is in my interest in the warrior ways of ancient Ireland and Scotland that all those things come together, the physical training and the importance of story.

As I wasn’t writing much about Gaelic spirituality at the time I started this blog, having started at a time of conflict, flux and burn out in the community and taking things more private for awhile, I have realized it might seem a sudden switch to some of my readers. While the intent of this was always to be about various aspects of the warrior path in my life and how they came together, the focus had been on fitness, self-defense and popular culture. That itself might seem quite a mix to some. But it really is in my interest in the warrior ways of ancient Ireland and Scotland that all those things come together, the physical training and the importance of story. furniture out of the way (come spring most of it will be moved completely out), we put down padded flooring, moved in the weights, benches, heavy bag. We added a pull-up and dip tower, as I have given up, for now, on finding the perfect bed frame to turn on it’s side. When things are moved out more we’ll have more open space, especially to work the bag, and probably get more equipment over time.

furniture out of the way (come spring most of it will be moved completely out), we put down padded flooring, moved in the weights, benches, heavy bag. We added a pull-up and dip tower, as I have given up, for now, on finding the perfect bed frame to turn on it’s side. When things are moved out more we’ll have more open space, especially to work the bag, and probably get more equipment over time.

McCone finds it likely that there were men who were never given inheritance who remained. In the tales Fionn is an example. He doesn’t speculate about women in the bands, but Nagy notes those associated with Fionn himself, especially his fosterers. (The Wisdom of the Outlaw) In most of the tales we have of women involved, with the exception of Fionn’s fosterers and Aoife, who is so named (Scáthach isn’t, but is clearly a woman warrior who is Outside the culture in question), the women likewise are only ban-fhénnid for the time they must be for revenge. (

McCone finds it likely that there were men who were never given inheritance who remained. In the tales Fionn is an example. He doesn’t speculate about women in the bands, but Nagy notes those associated with Fionn himself, especially his fosterers. (The Wisdom of the Outlaw) In most of the tales we have of women involved, with the exception of Fionn’s fosterers and Aoife, who is so named (Scáthach isn’t, but is clearly a woman warrior who is Outside the culture in question), the women likewise are only ban-fhénnid for the time they must be for revenge. ( ayed her boss Oscar Goldman, the theme came up a lot. He brought up her sensitivity to violence, the ways that caused the show to differ from the

ayed her boss Oscar Goldman, the theme came up a lot. He brought up her sensitivity to violence, the ways that caused the show to differ from the

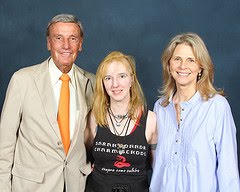

tos and paying for the autographs with her assistant, he has commented on the shirt (the shirts got many comments, actually…including one guy who did ask if I had more than one on Sunday, which I did, btw). Linda quoted the “siempre como culebra” and explained to him that it was from

tos and paying for the autographs with her assistant, he has commented on the shirt (the shirts got many comments, actually…including one guy who did ask if I had more than one on Sunday, which I did, btw). Linda quoted the “siempre como culebra” and explained to him that it was from  autographs and some photos with her. Oh, there was also a bit of “looking so forward to seeing you on

autographs and some photos with her. Oh, there was also a bit of “looking so forward to seeing you on  rength, especially one who told her that she helped her through a really difficult time in her life. This reflects what

rength, especially one who told her that she helped her through a really difficult time in her life. This reflects what  there. Yet, I did have a professional photo with a different photographer, who offered jpgs as well as prints, on the floor (the Terminator ones were where the panels were) with Lindsay Wagner and Richard Anderson. And the Terminator actors were all across from William Shatner and other Trek stars, so between the two the aisle there was jammed packed. We did manage to get back to se

there. Yet, I did have a professional photo with a different photographer, who offered jpgs as well as prints, on the floor (the Terminator ones were where the panels were) with Lindsay Wagner and Richard Anderson. And the Terminator actors were all across from William Shatner and other Trek stars, so between the two the aisle there was jammed packed. We did manage to get back to se e Bess and to see Michael Biehn. So, yes, I did get photos and autographs with two men, so see I’m not sexist because I have token male representation here! *snerk* Bess even asked us to pose with her for a photo for her FaceBook page!

e Bess and to see Michael Biehn. So, yes, I did get photos and autographs with two men, so see I’m not sexist because I have token male representation here! *snerk* Bess even asked us to pose with her for a photo for her FaceBook page! t Claudia Christian, of

t Claudia Christian, of  It reads:

It reads: Do I even need to say there are no words?

Do I even need to say there are no words?